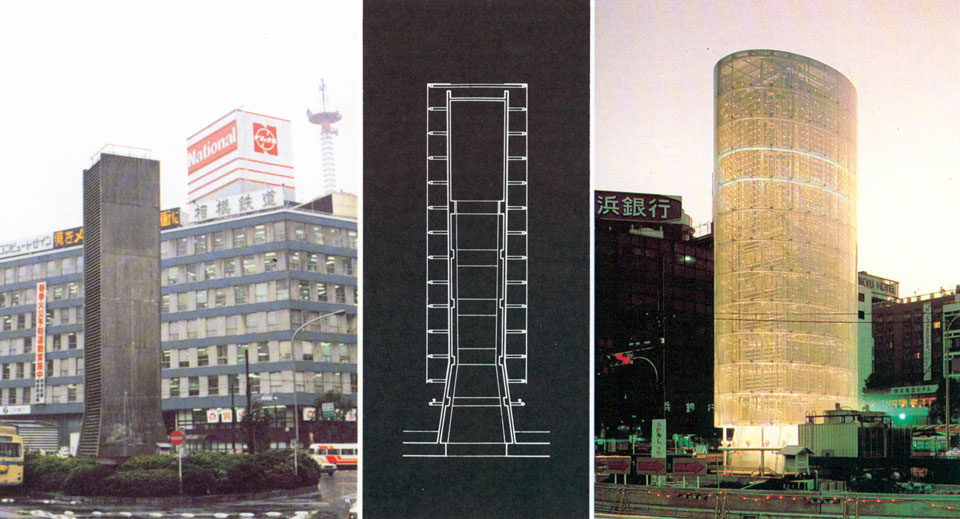

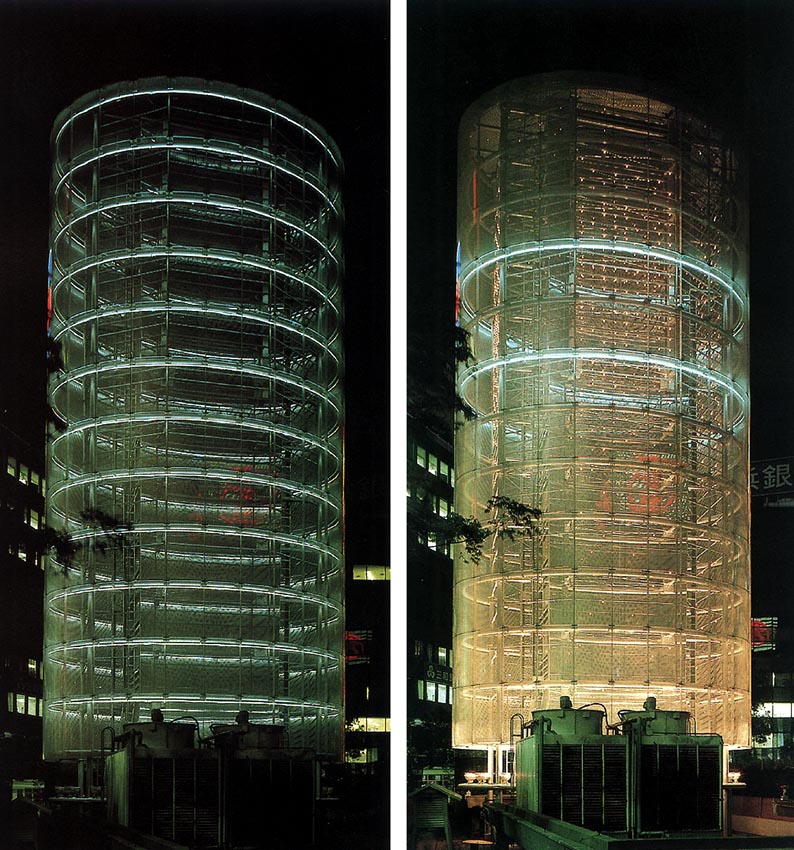

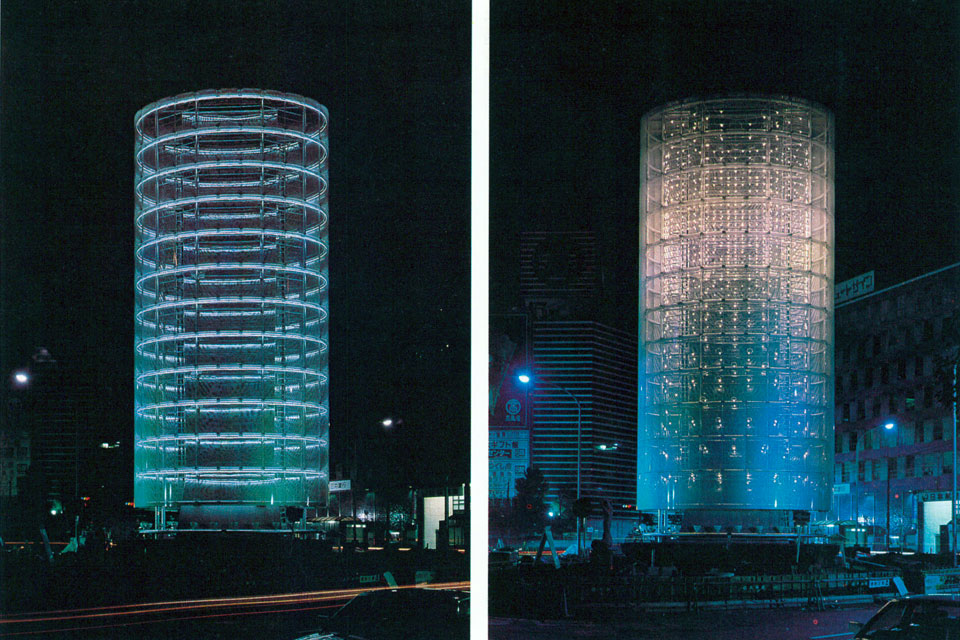

As dusk descended and Puerto Rico plunged into another blackout, I flipped through materials on contemporary architecture, interactive design, and energy. The light of an LED lamp illuminated Toyo Ito’s Tower of Winds, a project that reimagined a utilitarian water tank in Yokohama, Japan, as a kinetic sculpture interacting with its environment. Its perforated aluminum panels reflect the city by day, while a mesmerizing array of lights dances to the rhythm of wind and sound by night.

Completed in 1986, the Tower of Winds metaphorically represents Tokyo’s ever-changing winds, responding to their speed and direction with a dynamic light display. This transformative approach to design sparked my imagination as I sat in the familiar discomfort of another powerless evening. My thoughts turned to nuclear energy and a recent conversation with Mary and Jordan from the Fissionaries podcast by the Nuclear Energy Institute. They had asked me about public sentiment toward cooling towers, how these towering structures are often misunderstood, and how fear—not function—defines their public image.

Like in the continental United States, some in Puerto Rico remain tethered to an outdated perception of nuclear energy, associating cooling towers with risk rather than progress. Despite growing public support for nuclear energy, this fear persists and must evolve if we are to envision a more sustainable future for both the island and the nation.

metaphorical representation of Tokyo with its ever-changing never-ceasing winds. The tower

changes expression in response to winds’ speed and directions (Photos with courtesy of

Shinkenchiku-sha).

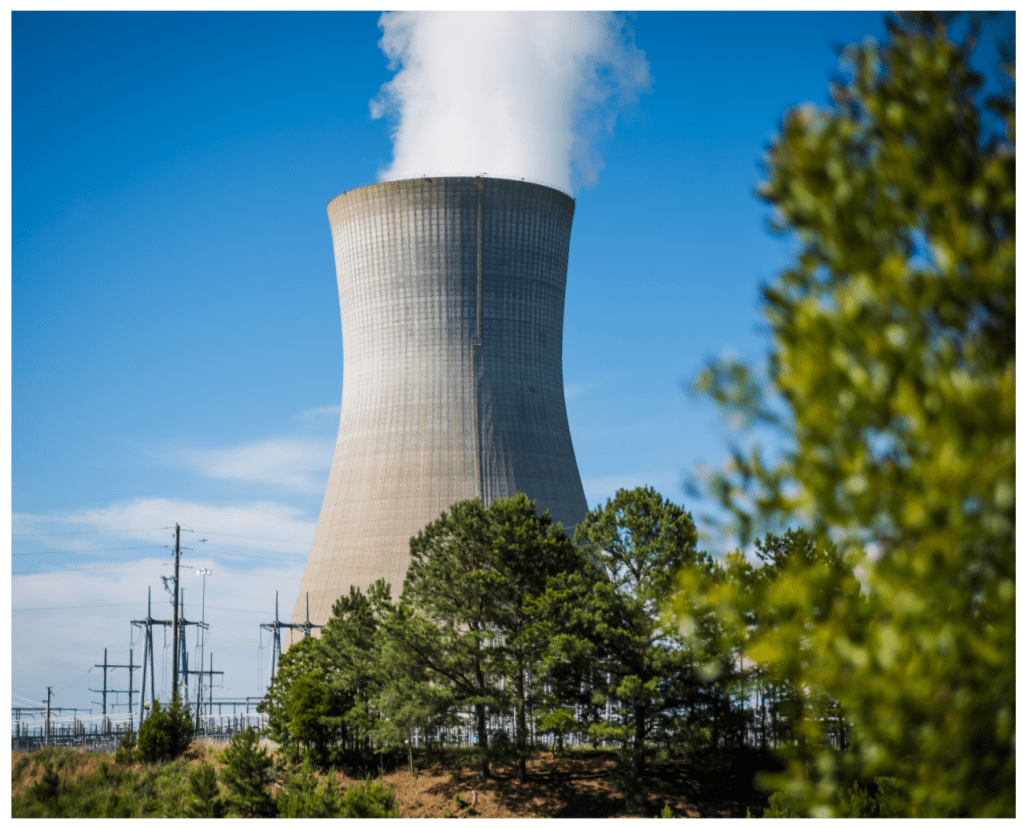

Cooling towers are critical to many power plants, including nuclear facilities, where they serve a singular purpose: to cool water used during energy production. This is achieved through heat transfer, where excess heat is released into the atmosphere as harmless water vapor. Those iconic plumes rising above cooling towers? They’re not smoke or pollutants—merely condensed steam, no different from the mist rising off a hot cup of coffee.

Yet, for many, cooling towers have become visual shorthand for nuclear danger. Their imposing size and association with the nuclear industry evoke anxiety fueled by decades of misinformation and sensational media portrayals. This fear is a barrier to progress in Puerto Rico, where atomic energy is not yet part of the energy landscape. The same holds true for the rest of the United States, where public sentiment often lags behind the realities of nuclear technology’s safety and environmental benefits.

If Puerto Rico is to embrace nuclear energy as a solution to its fragile energy grid, public understanding must shift. We must move beyond fear and see cooling towers as vital components of a clean and reliable energy system. Reflecting on Ito’s Tower of Winds, I saw an opportunity to reframe the narrative around these structures.

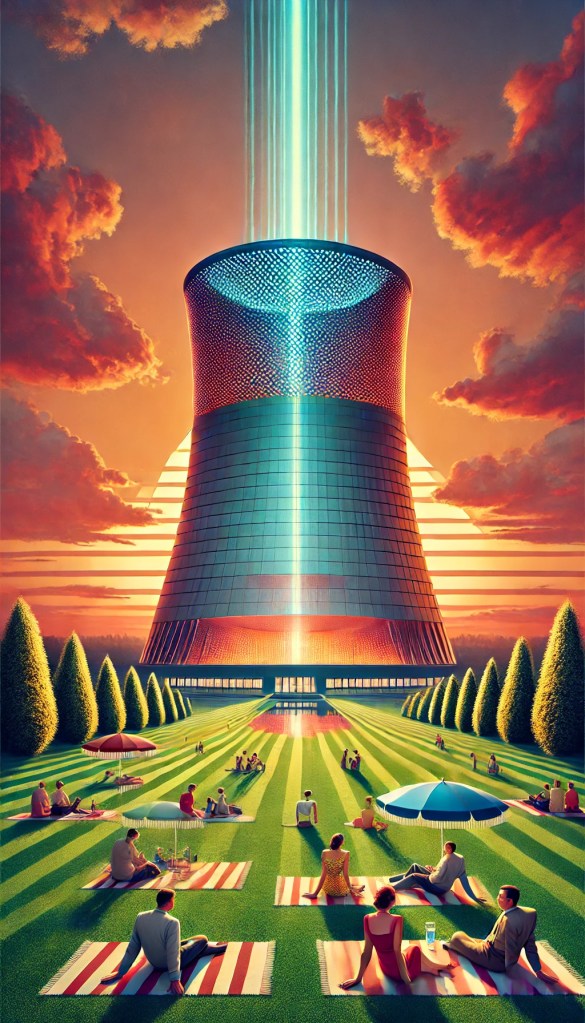

The Tower of Winds began as a utilitarian water tank, a structure built purely for function. But Toyo Ito transformed it into something extraordinary—an interactive sculpture blending technology, art, and nature. This approach could inspire a similar transformation for cooling towers. Imagine these concrete giants not as “industrial eyesores” but as canvases for innovation and creativity. Their surfaces could host vertical gardens, fostering biodiversity while softening their imposing aesthetic. Interactive light displays could showcase energy data, wind patterns, or solar cycles, turning the towers into dynamic landmarks that engage the community. By integrating art, technology, and environmental design, cooling towers could shift public perception from fear to fascination.

Redesigning cooling towers aligns with broader national and regional sustainability goals, demonstrating progressive environmental stewardship. Incorporating vertical gardens, solar panels, or wind turbines into their design could show how nuclear energy complements other green technologies. These modifications are tangible examples of how diverse energy solutions can coexist to combat climate change, reinforcing atomic energy’s role in a holistic approach to sustainability.

Cooling towers also have the potential to reflect and celebrate cultural identities, especially in Puerto Rico, where resilience and ingenuity are defining traits. Public art, historical narratives, or design elements could transform these structures into symbols of strength and progress. Across the United States, regional cultural themes could similarly personalize cooling towers, creating a deeper connection between nuclear energy infrastructure and the communities they serve.

Critics might argue that aestheticizing cooling towers doesn’t address deeper concerns about nuclear energy—safety, waste management, or disaster risks. These are valid points and must be addressed transparently. Public engagement must begin with education, ensuring communities understand the science and safety measures behind nuclear technology. Modern nuclear energy plants are designed with multiple safety features and have a strong safety record. Waste management remains a priority, with advanced technologies for recycling and disposal. These facts should be part of the public discourse to alleviate concerns. It’s crucial that the public is actively involved in these discussions and that their concerns are addressed transparently and respectfully.

Visual and emotional connections are equally important. People fear what they don’t understand, and this fear often stems from perception rather than reality. Reimagining cooling towers as accessible and inspiring landmarks can bridge the gap between technical education and emotional acceptance, making nuclear energy feel less alien and more integral to daily life.

In Puerto Rico, blackouts are a constant reminder of the urgent need for stable, sustainable, and resilient energy solutions. Nuclear power offers a path forward—not just for stability and sustainability but for economic growth. The industry can create jobs, stimulate local economies, and reduce energy costs. For instance, constructing and operating a nuclear power plant can create thousands of jobs and significantly boost the local economy. For this vision to become a reality, public sentiment must evolve. Cooling towers, often seen as symbols of industrial alienation, could instead become emblems of hope and innovation—monuments to a future where the island no longer lives at the mercy of an unstable grid.

This reimagining could help shift the national conversation around nuclear energy across the United States. Cooling towers need not be monuments to fear. Much like Toyo Ito’s Tower of Winds, they can be transformed into beacons of progress, blending necessity with artistry and symbolizing harmony between nature, technology, and humanity.

The future of energy isn’t about choosing between safety and beauty. It’s about blending them to create systems that are as inspiring as they are efficient. For Puerto Rico and the U.S., it’s time to rethink what we fear and embrace what we can achieve.

References

ArchIntoJapan. (2013, May 27). Tower of Winds. Arch Into Japan. Retrieved from https://archintojapan.wordpress.com/2013/05/27/tower-of-winds/

Cole, D. A. (2021, October 14). Cooling towers: What are they and how do they work? Duke Energy. Retrieved from https://www.duke-energy.com/blog/cooling-towers-what-are-they-and-how-do-they-work

Nuclear Energy Institute. (2024, November 10). Fissionaries podcast: Coloring outside the nuclear lines [Audio podcast episode]. In Fissionaries. Retrieved from https://open.spotify.com/episode/01Xhm9HJlGJ30Chv3jrvZN?si=jcvrAr64QQGYU0yIKpRDlg

Vallgårda, Anna. (2014). Giving form to computational things: Developing a practice of interaction design. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-013-0685-8